Mallee Dunefields of the Murray-Darling Basin

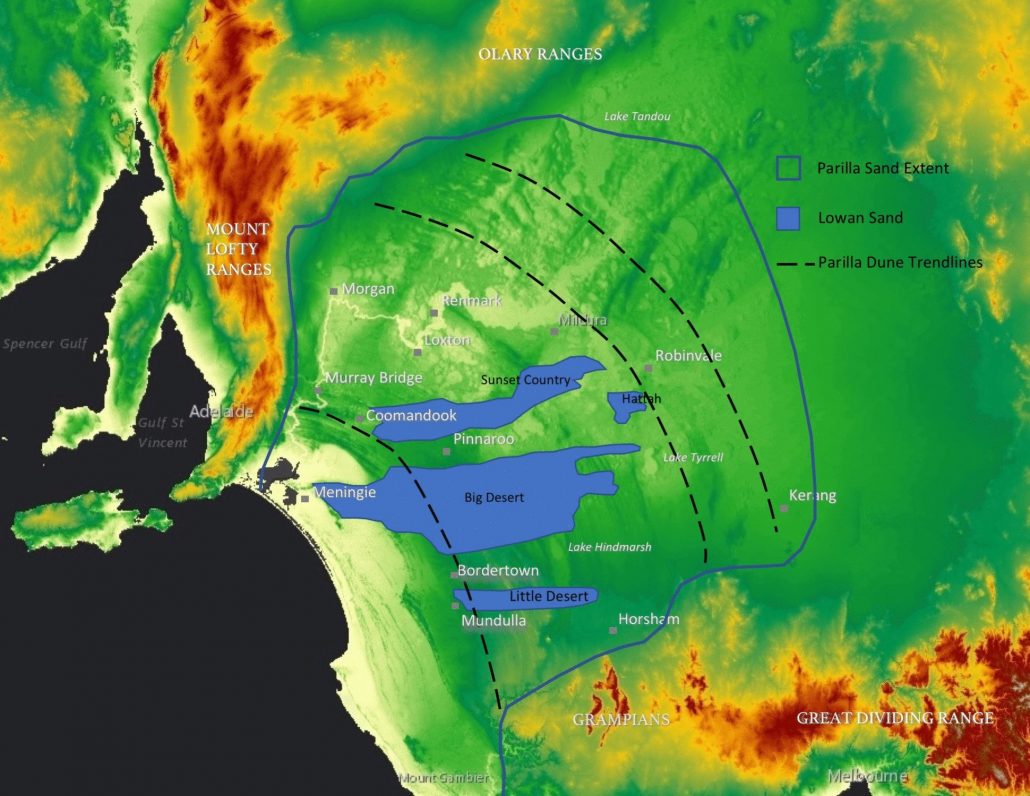

Dunefields extend over most of the south-west Murray-Darling Basin.

The dunes and their soils have shaped the vegetation, land use and history of the region. They are wind-blown sands that derive from the underlying Parilla Formation.

Parilla Sand

About 50 million years ago, as Australia was separating from Antarctica, the Murray Basin formed as a broad gulf in south-central Australia. The gulf extended from the Great Divide in Victoria and New South Wales across to the Olary Ranges and Mount Lofty Ranges in South Australia.

After a series of depositional phases, a final marine transgression occurred in the late Pliocene (7.2 to 5.4 million years ago) when the sea reached north of Mildura and east beyond Kerang.

The coastline of the gulf formed an arc that trended north from the Grampians and west to the Mount Lofty Ranges. The Parilla Sand was laid down along this coastline and included near-shore marine sediments and a distinctive coastal barrier dune.

Over the next 2 million years the shoreline periodically moved, stabilised and moved again in an overall retreat to the south-west. In each period of stability, a new coastal barrier dune formed.

This resulted in a continuous series of over 600 parallel ridges. The Parilla Sand is now mostly buried, but many ridges are still visible. Ridges rise from a few metres to more than 20 m and are typically spaced 2-3 km apart. Some individual ridges can be followed over distance of 300 km.

The Parilla Sand is also known as the Loxton-Parilla Sand. It is coarse and gritty, and rich in clay. It is typically pale brown to rusty red-brown in colour.

Parilla Sand on the west shore of Lake Hindmarsh, Victoria (photo Lance Lloyd).

The Parilla Sand rarely outcrops in the mallee. The stranded coastline ridges are most noticeable as periodic hills when travelling east-west along the Dukes Highway or Sturt Highway. A distinctive example is the steep Lawloit Ridge between Kaniva and Nhill.

The vegetation of the ridges is distinctive, supporting Buloke (Allocasuarina leuhmanii), Yellow Gum (Eucalyptus leucoxylon) and Native Pine (Callitris gracilis) in contrast to the adjacent mallee.

Woorinen Sand

After the sea retreated, about 2 million years ago, the Parilla Sand was exposed to wind erosion during arid glacial periods.

Sand from the Parilla Formation was mobilised and reworked with clay from the ancient Lake Bungunnia and limestone from the exposed southern coastline. An extensive wind-blown dunefield developed over most of the western Murray Basin. This is the Woorinen Sand.

The dunes are low with rounded crests that are generally 2-10 m high. They are evenly spaced and linear, running east-west. The soil is orange on the sandy ridges and pale in the limestone-rich swales. The dunes are stabilised by their clay and limestone content.

The east-west dunes of the Woorinen Formation south of Loxton, South Australia. The diagonal outline of the underlying Parilla Sand ridges is visible (Google Maps).

This Woorinen Sand makes up most of the cropping country in the Murray Mallee. It is also the principle soil of the irrigated country along the River Murray west of Swan Hill.

Native vegetation is mainly mallee woodland including Ridge-fruited Mallee (Eucalyptus incrassata) on the dunes and Yorrell (Eucalyptus gracilis) in the swales.

The rounded east-west crest of a Woorinen Sand dune north of Lameroo, South Australia.

Lowan Sand (Molineaux Sand)

More recently, a second dunefield formed in the Murray Basin from erosion of the Parilla Sand.

The Lowan Sand dunefield occurs in three extensive sheets that stretch eastwards from South Australia into Victoria: the Sunset Country from Karoonda, the Big Desert from Meningie and the Little Desert from Mundulla.

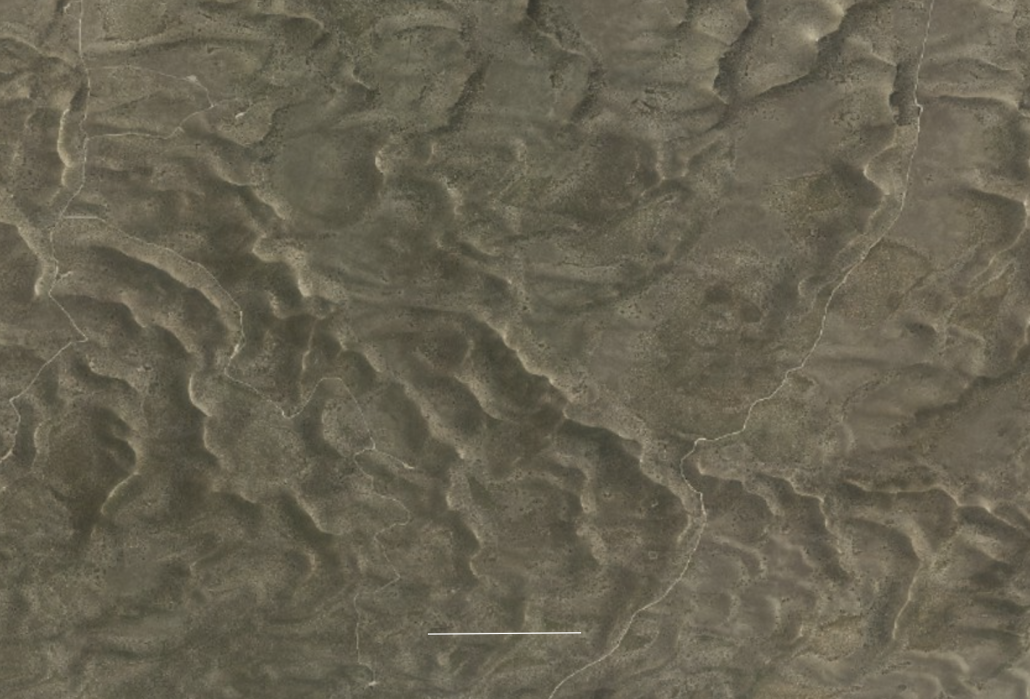

The Lowan Sand is pale, glassy, freely draining and mobile. The dunes rise steeply in overlapping parabolas that point to the north-east. Individual dunes can reach more than 40 m high. The sand is white in the south and becomes slightly redder in the north.

The jumbled, parabolic dunes of the Lowan Sands in Ngarkat Conservation Park, South Australia (Google Maps). The white bar is 1 km.

The Lowan Sand seems to originate from erosion at specific elevated localities, where wind deeply stripped the Parilla dunes, resulting in a distinctive nutrient-poor siliceous sand.

The Lowan Sand is called the Molineaux Sand in South Australia. It supports native vegetation adapted to the nutrient-poor, freely draining soil. In the south this is mainly heath, which is a highly diverse community of tough, often small-leaved, low-growing shrubs. In the north the heath has a mallee overstorey, mainly Ridge-fruited Mallee and Scrub Cypress Pine (Callitris verrucosa).

Heath vegetation on Lowan Sand in Billiatt Wilderness Area, South Australia.

The Desert Country

Even by the Indigenous Ngarkat and Wurega people, the Lowan Sand dunefields were sparsely populated.

Settlers characterised this region as uninhabitable ‘desert’ due to the absence of water or feed for horses. Crossing the Ninety Mile Desert was treacherous and avoided by taking routes along the Coorong or Murray.

Attempts to farm the Desert Country consistely failed, despite the region experiencing good rainfall of 300 to 450 mm/year. Soaks were sparse and unreliable. Nutrients were depleted after a few crops. Due to copper deficiencies, stock grazed on the scrub or pasture quickly became sick.

It was not until the 1950s that research into micronutrients in South Australia determined that supplements of copper, zinc and molydenum were the key to opening the region. Development quickly followed, with support from the AMP scheme.

The AMP scheme also promoted development in Victorian mallee. However, development of the Desert Country was mostly postponed. By the 1960s the growing conservation movement successfully argued for its preservation.

The contrasting policies of South Australia and Victoria are evident in the abrupt western edge of several Desert Country reserves along the border.

The Lowan Sand within the Sunset Country at the South Australian / Victorian border (Google Maps)

Further Reading

Bowler, J.M., Kotsonis, A., Lawrence, C.R. (2006). Environmental evolution of the Mallee region, Western Murray Basin. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 118 (2): 161-210.

Durham, G. (2001). Wyperfeld Australia’s first mallee national park. Friends of Wyperfeld National Park Inc.

McLaren, S., Wallace, M.W., Gallagher, S.J., Miranda, J.A., Holdgate, G.R., Gow, L.J., Snowball, I. and Sandgren, P. (2011). Paleographic, climatic and tectonic change in southeastern Australia: the Late Neogene evolution of the Murray-Darling Basin. Quaternary Science Reviews 30: 1086-1111.

Reuter, D. (2007). Trace element disorders in South Australian agriculture. Unpublished note of the Primary Industries and Resources South Australia, Adelaide.

Tiver, N.S. (1986). Desert conquest: A review of the main events which contributed to the development of the Ninety-Mile Desert. AMP Society, Adelaide.

Thanks to Steve Barnett for reviewing a draft of this article.